塞罕坝精神振兴的大地

——The spirit of Saihanba's rejuvenated land

Towering trees now dominate Saihanba, an oasis in Hebei Province that was once a desert.

On a winter night when the outdoor air temperature dropped to around 40 degrees below zero Celsius, a group of men huddled in a small thatched hut on a vast piece of desert land in northern China. The hut had no door, and the wind was raging.

The men – about 20 of them – found it hard to sleep. They wore woolen hats and cotton clothes as they rested on mats on the ground, trying in vain to fend off the biting cold.

Then, some of them came upon an idea. They threw some bricks and stones into the campfire and took them out before they became too hot. They used those "baked" bricks and stones as warmers in their quilts.

It was not a story of one night, but of many nights. For many of these young men, this hard life lasted many years, even more than a decade.

Saihanba's winter can be extremely cold.

Stopping desertification

All this happened 60 years ago, on a high plateau in Hebei Province that often produced sandstorms to the north of Beijing, threatening the Chinese capital's ecological environment.

The 93,000-hectare high plateau area called Saihanba used to be the seat of vast primitive forests in the 17th century. The name, a combination of Chinese and Mongolian languages, literally means "beautiful highlands."

By the end of the 19th century, however, the forested area had lost its former luster with the decline of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Rampant felling of trees toward the end of the dynasty resulted in gradual soil erosion and desertification.

In the 1950s, the deserted land, with an average altitude of 1,500 meters and a straight-line distance of about 200 kilometers from low-lying Beijing, posed an immediate threat to the capital's environment: It was like someone pouring sand down to a courtyard from atop a roof.

Pioneers irrigate saplings at a mechanized forest farm in Saihanba in this file photo.

Despite economic difficulties in the 1960s, China decided to set up a state-owned mechanized forest farm in Saihanba to combat desertification by cultivating artificial forests.

The aforementioned men squeezed into the small hut were among the first batch of 369 pioneers who answered the nation's call and settled in Saihanba at a time when even birds had a hard time finding trees there to perch on. The young pioneers had an average age of below 24, and yet they braced themselves for extreme hardships with a mind of steel usually associated with a more mature age.

Today's Saihanba has become a haven for forests and biodiversity. In 2017, it won the UN Champions of the Earth Award for its contribution to the restoration of degraded landscapes.

Sixty years have passed, and Saihanba has become the world's largest artificial forest with a plantation area of 1.15 million mu (76,666 hectares). To be specific, the rate of forestation in Saihanba surged from 11 percent in the 1960s to more than 80 percent at present. In 2017, Saihanba won the UN Champions of the Earth Award for its contribution to the restoration of degraded landscapes.

Also in 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping put forward the "Saihanba spirit" for the first time. A key element of the spirit is the pioneers' dedication to and historic achievements in the country's green development under the guidance of the Communist Party of China.

Last year, President Xi visited the Saihanba mechanized forest farm and called the Saihanba spirit an exemplar of the country's construction of ecological civilization.

Indeed, with the relentless efforts of three generations of foresters, Saihanba has turned from a desert land into a highland oasis, providing precious water and oxygen resources for nearby regions and people.

Now, Saihanba can store 284 million cubic meters of water, absorb 860,000 tons of carbon dioxide, and release nearly 600,000 tons of oxygen every year. Moreover, the average number of days with strong gales has decreased from 83 to 53 annually.

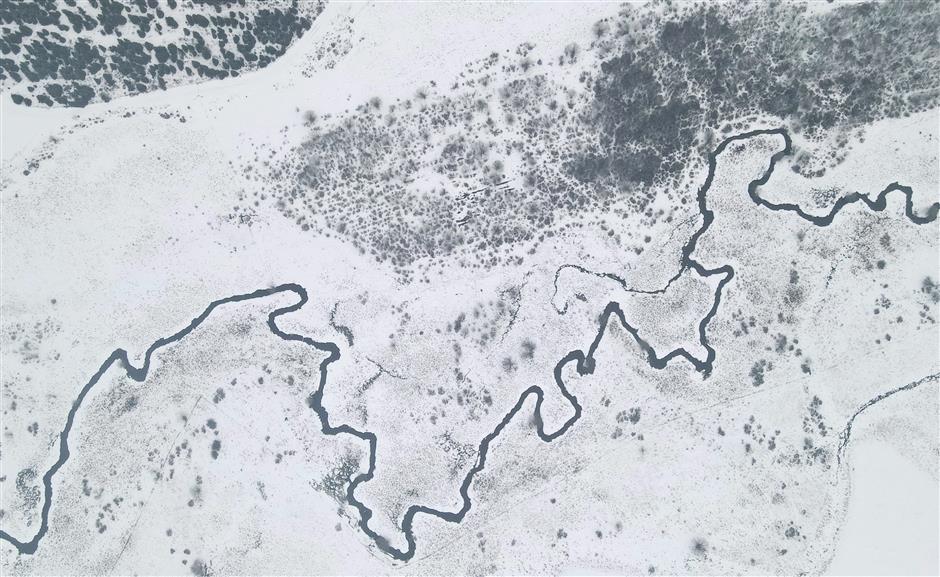

Above and below: The beautiful landscapes at Saihanba today. Saihanba now can store 284 million cubic meters of water, absorb 860,000 tons of carbon dioxide, and release nearly 600,000 tons of oxygen every year.

Shang Hai Memorial Forest

In the beginning, things were difficult for the first generation of foresters at Saihanba. They planted many trees, but most died. It was a trying moment for Wang Shanghai, the first Party secretary of the Saihanba forest farm, who headed the 369-member pioneering team.

In 1962, 40-year-old Wang was already a bureau chief in charge of agriculture in Chengde City, which administered Saihanba. He and his family lived in a cozy house in the city. When the Party tasked him with the responsibility to head the future forest farm in Saihanba, he did not hesitate. He even moved his whole family to the farm. The living conditions were so harsh on the farm that his kids often suffered from malnutrition.

"His kids wore worn-out clothes and looked thin and pale all day long," recalled Chen Yanxian, one of the first-generation foresters. "Without enough food, his kids often said they were hungry. They were indeed pitiable."

In the first two years of settlement at Saihanba, Wang and his team found that only 5 or 8 percent of their planted trees had survived. One reason was that saplings transported from other regions were not necessarily accustomed to local natural conditions. Another reason was that imported machines were not perfect in matching local geographic features.

In the face of failures, some college students and farm workers who came from cities felt discouraged and thought of giving up their efforts on the farm.

But Wang never gave up. From the failures of the first two years, he learned how to cultivate saplings on Saihanba's own territory and how to adapt machines to local conditions. In 1964, he and his team chose a piece of land called Matikeng for a new round of experiments. The result was surprisingly rewarding: About 99 percent of the planted deciduous pines had survived.

It was the victory of a scientific spirit, and the victory of a cause to improve the planet's ecological environment against extremely harsh conditions.

In 1989, Wang died of cardial infarction in a hospital in Chengde. His will: To be buried in Saihanba.

Now, he rests in Matikeng, among a memorial forest dedicated to him. He has given his life to the creation of a miracle in restoring degraded land to its natural glory.

Workers dig out stones in a hope to create tree pits on a mountain slope at Saihanba.

Trees from stones

Inheriting Wang's scientific and sacrificial spirit are a new generation of foresters who have discovered ways of planting trees on steep stony slopes in Saihanba.

On some slopes, there's only a thin layer of earth – about 5cm to 10cm deep. Below the shallow earth lie irregular stones. "To cultivate a forest on such slopes is like growing trees on stones," said Yan Liwen, a farm manager.

Planting trees on stony slopes is a world-class challenge. What foresters in Saihanba did in recent years was to dig out certain stones to create a reasonably large square pit for each sapling. Then they filled the pit with earth fetched elsewhere and covered the sapling with plastic film and straw mats to hedge against weathering and water loss.

It was easier said than done. Xie Min, another farm manager, led a team of foresters onto a stony slope in 2015 in the hope to plant trees there. On the spot, he found that machines could not climb up such a steep slope, so he and his team members could only use spades. The mountain stones were so hard that every swing of a spade would produce a strong reactive force that caused acute pain in the workers' hands.

Undaunted, Xie led more than 60 workers to dig nearly 90,000 tree pits in over 20 days. They succeeded.

"By 2030, we expect to increase the rate of forestation to 86 percent, which means all of Saihanba will be covered in greenness except for roads, rivers, wetlands and firewalls," said Chen Zhiqing, head of the mechanized farm.