今日上海

讲述和捍卫历史:前上海犹太难民索尼娅获得“丝路友好使者”称号 - 2022年06月10日

'Shanghai baby' honored for devotion to city's Jewish refugee heritage

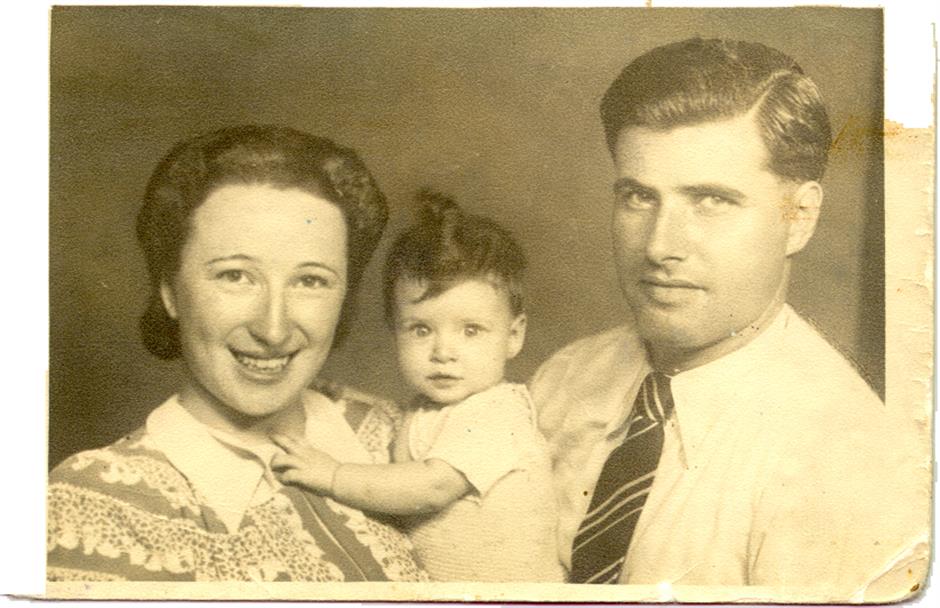

Sonja Muehlberger arrived in Shanghai in 1939 in her mother's womb, unaware that she would become an eyewitness to a unique Jewish experience in Shanghai.

And, more importantly, she would one day go on to share her first-hand experience and research with people around the world. Part of Muehlberger's efforts evolved into the Wall of Names of Jewish Refugees in Shanghai during the 1930s and 1940s, a structure installed at Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

This week, the 83-year-old, who has lived in Berlin since returning with her family in 1947, was named as one of 12 winners of the second Silk Road Friendship Awards. They were co-hosted by the China International Culture Exchange Center and Global People, a journal published by People's Daily.

"It's necessary to speak about the past and to stand up again, because new Nazis are emerging," the energetic German teacher, lecturer and author told Shanghai Daily via WeChat immediately after the awards ceremony.

"As a former European Jewish refugee and a friend of Chinese people, to maintain peace together is the purpose of this award, and our genuine wish," she said.

Her brother, merely a 2-year-old on leaving Shanghai, once asked Sonja about when she started thinking about and working on a theme about Shanghai.

"I told him I never forgot anything about Shanghai," she said. "When it comes to this topic, I can keep going for hours."

She did, especially when recounting her childhood stories in Shanghai, which she calls "my birth town." It was in Hongkou District in Shanghai that her mother told her many fairytales, including Snow White. It was also here that one day her father asked her to put her hands into a basin of snow he had collected on the rooftop, to get a sense of snow.

"Lots of new houses have sprung up in the area where we used to live. The streets are wider today and there are trees on them," she wrote about her 2012 summer trip to her birth town, one of the nine times she has revisited since 1998.

The house where she lived was still there on that first trip, though the city had changed dramatically.

"It had changed a lot but it also looked familiar," she told Shanghai Daily about that exciting homecoming.

"I knew the street so well that I could just walk from the refugee's museum to where we used to live. I could recognize many old buildings where friends and acquaintances lived. I can still remember and tell you everything about the area."

She was still excited when recounting the excitement of her first revisit, but even more so when telling the story of meeting the Chinese people again for the first time in 1951.

The International Youth Festival was held in Berlin that year, and China also sent a delegation of children around her age. She was so excited that she exchanged her young pioneers' red scarf with a Chinese girl from the delegation.

"It's still very emotional when I talk about it now," she said, her voice trembling. "That was the first time I met Chinese people again after we returned to Berlin in 1947."

Curious since childhood, young Muehlberger paid attention to her surroundings and asked many questions. Some were answered immediately by her parents, and others she understood in later years or discovered from her own research.

She was Baby Krips on her birth certificate for nearly three months, until her father got her passport from the German Consulate General in Shanghai, then under the Nazi government.

"He was a little scared, but he was determined to get a passport for me," she recalled. "He was determined to get a name for me."

The obsession with names came from her father's four-week experience in Dachau, the first concentration camp.

"There, Jewish people had no names, were merely reduced to numbers," she explained. "For my father's entire life, he never forgot his number. It was inked in his head. That also impacted me. Why did people become numbers? People should have names."

Her parents met each other at a sports club in Frankfurt. When her father was taken to the concentration camp in 1938, her mother found there was only one way to secure his release – providing valid travel papers, and "Shanghai was the only place in the world that stood open to German Jews."

Her mother managed to obtain the required paperwork from the Chinese consulate in the Netherlands. And the young couple boarded a ship in Genoa on March 29, 1939, with Sonja already in her mother's womb.

They named her after Sonja Henie (1912-1969), a Norwegian figure skater, actress and a three-time Olympic champion.

Her father's obsession with names also impacted her, and partly encouraged her to start her research into this history, including collecting and verifying the names of Jewish refugees in Shanghai.

Chen Jian, curator of Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, calls Muehlberger a "Shanghai baby" and a person who is "extraordinarily energetic still at the age of 83."

"She has such a special tie and gratitude for Shanghai. She has collaborated with our museum over the years, and is the leading contributor to the list of names inscribed on the wall at our museum," Chen said.

"Many institutions debate the exact number of Jewish refugees in Shanghai, which is why the name list wall is very important. We want to show facts as they are by imprinting all the names that can be tracked down, and they continue to increase."

There were 13,732 names on the wall when it was first erected in 2014, 18,578 when the museum was expanded and the wall updated in 2020. Now, Muehlberger's list has expanded to nearly 20,000 names.

"The count is different in speeches and books by different academics or institutions, 30,000, 35,000 or 15,000… It depends on how they define refugees. Which ones do we count as refugees?" she said.

To her, what's important is sharing this history and giving everyone the names they deserve, rather than a total count.

When giving Muehlberger her friendship award, the organizers said that she has "burst into the flower of peace. She wrote down history and also gratitude with her own experience."

They added, "At the darkest moment in life, she bore down in her mind China's hug and reception. The suffering could not erase the virtues of humanity. The longing for living and for the future is the strength for us to go ahead."