今日上海

当艺术预见科学…… - 2016年05月20日

Experimenting with science to create art

ART, combined with science, is in vogue at the international art scene, but it is a struggle for many formally trained Chinese artists who lack a thorough knowledge of mathematics or physics.

Not for Shang Tun, however. Shang is among few Chinese contemporary artists whose brain oscillates swiftly between art and science. A veteran paraglider, he is also good with machines.

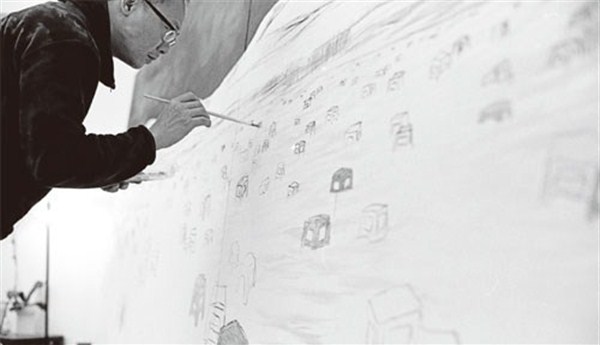

Shang’s solo exhibition at Don Gallery, which is in an historical building, traces the origins of his art. The featured works on display include paintings, videos, installations, photographs and performance art, in addition to archival material such as his manuscripts.

His works contain a heavy dose of rich metaphors and unconstrained imaginations. Basic commodities, such as lifebuoys, tissues and plastic stools, become motifs in his work. These materials and their derived symbols have been translated into an artistic language with unique expressiveness. For example, when the familiar forklift is viewed in a fragment it resembles a leaf.

Born in 1968, Shang’s life — like many people of his generation — was filled with twists and opportunities, closely bound to China’s political and economic growth. His father was a well-known professor at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Art and understandably, art came naturally to him.

After graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, Shang returned to Guangzhou. Over the next 20 years, he ventured into business, following the course of “making money” rather than “making art.”

But eventually he had to give in his inner feelings. “Andy Warhol said ‘good business is the best art.’ I did not want to be a starving artist. I wanted to fully realize what I want in art without any financial constraints.”

Shang’s artworks reflect that feeling — strong, masculine and scientific. Some of the works are heavy on physics such as the periscope principle.

In the main room of he gallery, an installation titled “Periscope Forms a Part of the Respiratory System” connects the viewer to the landscape constructed by the artist. Through the refraction of light, it transforms the space into a virtual blue cloud-speckled sky.

The middle room of the gallery is a studio, filled with stuff that is relevant to Shang’s work, including drawing tools and materials, photographs, small installations and models.

An electrical equipment takes the viewers to explore the artist’s “temple of mind.” A separate area is converted into a video room screening his latest audio-visual works.

“You’re right, I am good at physics and math,” he says. “If I hadn’t been an artist, I would have been a physician.”

Shang confesses that there is something inborn in his love for mechanics. “I would buy a small vehicle and then refit and modify it,” he says.

That might perfectly explain his passion for paragliding, which he took up almost a decade ago.

“When I take to the skies, I have to get every small detail right — from varying degrees of speed and direction of the wind, the geography on the ground to the hand movement,” he says. “My brain is like a fast-running computer. But that feeling in the sky is terrific. When you are up in the air, everything around you seems to vanish, except the sound of the paraglider’s rope ‘slicing the wind’.”

Yet despite being a veteran paraglider, Shang had his “dangerous moments” in the sky. “The rope got entangled in my body and I was unable to make adjustments in the air. Luckily I managed to get my hands on the belt of a back-up glide at the last moment — only 15 seconds before I hit the ground,” he recalls.

Shang’s art is heavily influenced by his deep interest in the social and cultural development of the ordinary people and the stark reality of a consumer-oriented society in China. He highlights the contrasting realities of the toiling workers through his art that is either metaphorical or straightforward.

He shuttles between the world of the real and the virtual space, weaving sky and data together, and using his own body and other media sourced from Google Earth and GPS to bring his pieces to life.

Shang uses an unmanned aerial drone for art. One of his video has two different footages, one captured by an airborne cameraman and the other by a camera fitted on the drone.

“Most of us think that the unmanned aerial vehicle might be more accurate, but the result is quite interesting. The drone actually adjusts its route to save battery power,” he says.

One of his installations features a part of a forklift weighing about 400 kilograms.

“I signed an agreement to cover any losses if this building collapsed because of this gigantic thing,” he says. “Sounds funny, doesn’t it? This is also one of the attractions of being an artist.”