今日上海

三百多年历史的“Grand Tour”依然进行时…… - 2016年07月22日

Touring tradition inspires local author

INSPIRED by a former rite of passage for Europe’s upper-crust and literary elites, Shanghai writer Chen Danyan just returned from a three-week journey through the Italian region of Tuscany.

“For me, it was a dream come true,” says Chen in an interview with Shanghai Daily.

The 57-year-old could hardly contain her excitement as she recounts her eye-opening sojourn, modeled after the bygone tradition of the Grand Tour.

Such tours gained popularity in the 16th century, and were meant to expose aristocratic young adults to the legacies of antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Traveling around the Continent was also a way for the youths of polite society to familiarize themselves with the languages, customs, artworks, architecture and geography of the Continent — all cornerstones of a classical education at the time.

As the Grand Tour tradition developed over the following centuries, Italy gained a particular allure among many of the West’s greatest authors. Byron, Shelley, Goethe, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Wilde, Keats, Browning, Dickens, Montaigne, George Sand, Nietzsche, Thomas Mann, Stendhal and Mark Twain, to name just a few, all found inspiration in the country’s history, culture and landscapes.

For Chen, understanding the history of these tours and their relationship with Western literary culture added significance to what could otherwise have been an ordinary holiday.

As her own literary career began to take shape in China during the 1980s, an era when large numbers of translated Western classics and popular novels became available following the upheaval of the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), Chen was exposed to many of the writers listed above. Their writings and world views, she explained, greatly influenced her own maturing work.

In the footsteps of giants

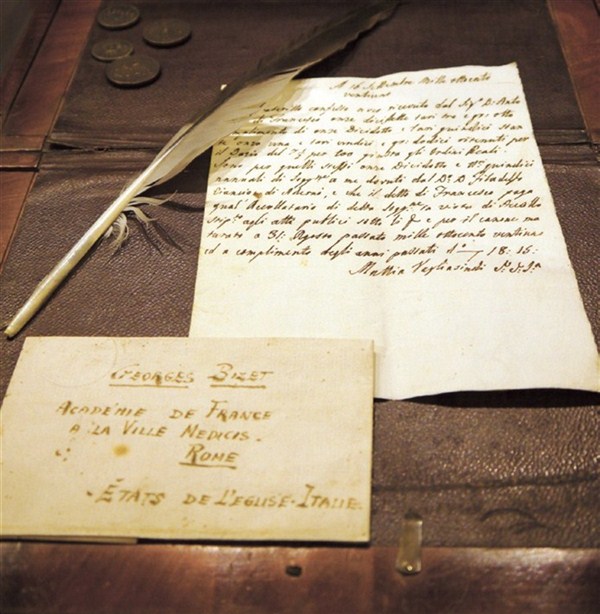

At Poppi Castle, Chen was allowed to pursue a library of ancient books from the 16th-18th centuries. This library is also where an original Italian text of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” is kept.

Often described as the “father of the Italian language,” Dante was one of the first writers of his time to eschew Latin in favor of a vernacular writing style. He is said to have conceived of his famous poetry cycle during his exile between 1308 and 1321.

Chen described placing her Chinese-language version of Dante’s “Inferno” next to the original sheepskin scroll — specifically Canto XXXIII, which references the castle — and being moved to tears by the beauty of the language and her feeling of closeness to this titan of world literature.

“For years, I’ve formed a habit of reading along the way on my tours. To read the paragraphs at the place mentioned in the book gave me a thrill. I was just a teenage girl when I first read them, and now as I re-read them with the heart of an middle-aged woman, it was like traveling back in time — what could have been a better experience than that!” Chen exclaims.

Like her literary predecessors, Chen’s own grand tour also provided the opportunity to learn about the art and music of her destination.

Chen stayed in the Sanctuary of La Verna for 11 days. Overlooking a sheer cliff and wrapped around by a surrounding wood, she found the sanctuary a whole treasure trove of art, culture and history.

During the days she learned about traditional copperplate engraving techniques used to make illustrations for European novels under the guidance of teachers from the Florence Academy of Fine Arts; she did field drawings with the local painters and completed her first oil painting on a real canvas painting stand; she also took several private lessons on a 14th-century pipe organ in the sanctuary chapel.

At nights when sleep failed to visit, she tucked her in a blanket and re-read Browning’s “Sonnets.” And when dawn broke, she closed her edition of Montaigne’s “The Complete Essays.”

One of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance, Montaigne is best known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. Chen says she remembered the day before she was about to set off from Shanghai, French translator Ma Zhenpin brought her a book of essays by Montaigne entitled “The Journal of the Journey to Italy.”

“He told me Montaigne undertook a journey to Italy in 1580 and wrote down in great detail what Italy was like at that time. Though he did most of Montaigne’s translation from French to Chinese, he’s never been to Italy. He hoped I’d come back and tell him how much Italy and the Italians have changed from the 16th century,” Chen says.

But Montainge wasn’t the only foreign writer who found inspiration in Italy. German writer Goethe’s journey to Italy gave ideas to “Faust;” Wilde finished his last book “De Profundis” and eventually passed into eternity in a hotel room in Paris; Gogol completed the first part of “Dead Souls” during his tour of Italy.

Chen says she grew up reading the Chinese translations of the works of European writers. She hoped her Grand Tour of Italy could not only be a journey to rediscover her favorite works, but also a Chinese writer’s salute to the European classics as well as the Chinese translators whose dedication played an important role in culture exchange.

At the moment, Chen has planned to go on three more Grand Tours of Italy in the following months, reading and learning along the way by visiting the old residences of great writers and putting flowers on their graves.

At the same time, she hopes to collect the matching works of senior Chinese translators like Fu Lei, Cao Ying, Tu An and Mu Dan, while conducting interviews to analyze the confluence and influence in writing and translation. And in the end, a book will be done and all the photos, journals and notes will take part in the event for Italy on the Grand Tour Exhibition in October.