今日上海

中国文学作品对外出版遇翻译瓶颈 - 2016年12月09日

China writers suffer from lack of good translations

JEREMY Stevenson, an American who likes to read, got interested in Chinese novels after reading a translation of Liu Cixin’s “The Three-Body Problem,” which won the Hugo Award for best science-fiction book in 2015 and sold over 110,000 English-translated copies since it was published in the United States in November 2014.

“Once I started reading some translated contemporary Chinese fiction, I got fascinated, but not many are available,” he said. “Very few are in big bookstores, many are sold out or unavailable on Amazon, and some have been translated so roughly that I couldn’t get through them.”

Yes, that’s a problem. Many of China’s best literary works go mostly unnoticed overseas because of a translation bottleneck.

The Shanghai Translation Grants, established in 2015, were created to encourage more and better translations of Chinese books.

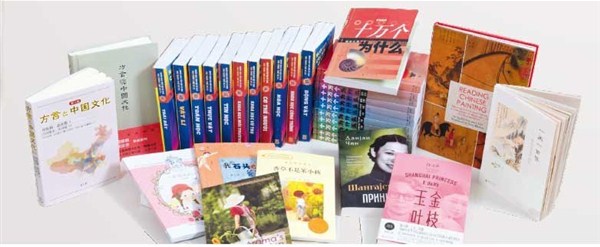

The program recently announced this year’s five winners — two books in English, one in Vietnamese, one in Serbian and one in Japanese. They include contemporary literature, art history and children’s books.

The grant is awarded to both published and unpublished translations, and this year’s winning books have all been published in their respective countries.

Retired British diplomat Tony Blishen, who lived and worked in Beijing in the mid-1960s, was behind two of this year’s winners — “Aroma’s Little Garden” by children’s book author Qin Wenjun, and “Reading Chinese Painting: Beyond Forms and Colors, a Comparative Approach to Art Appreciation” by Sophia Suk-mun Law.

Blishen said he considered the translation of Law’s book more than just a linguistic translation, but rather an education because the terms and concepts in Chinese and Western art history are very different, making it often difficult to find the right English words to express a Chinese idea.

Vietnamese professor Nguyen Van Mau led a team to translate the series of science books for children entitled “A Hundred Thousand Whys.”

Serbian publisher and translator Dragan Milenkovic was awarded for his translation of “Shanghai Princess,” a novel by Shanghai writer Chen Danyan.

A team of five Japanese translators won with “Dialect and Chinese Culture,” the result of in-depth research by professors Zhou Zhenhe and You Rujie.

The Shanghai grants typically honor foreign translators with strong Chinese language experience, allowing them to deliver translations that are idiomatic and culturally accurate.

Talented foreign translators

“Giving grants to those who can translate Chinese into their native languages is helpful in expanding the influence of Chinese books and Chinese culture overseas,” said Xu Jiong, head of the Shanghai Press and Publication Bureau that oversees the grants.

“They are intended to encourage and support foreign translators who are both talented and passionate about introducing good Chinese works to readers in their home countries. They tend to have a better understanding about the kinds of writing style their readers want.”

Dave Haysom, who runs the website Paper-republic.org and the magazine Pathlight, both dedicated to promoting Chinese literature to foreign readers, said it is crucial to understand target readers. Paper Republic organizes an annual publishing scholarship.

“These kinds of grants can certainly be helpful, and the money needs to be used in the right way if it’s going to really have a positive impact,” Haysom explained. “One of the most productive ways to achieve that is to forge closer links with foreign publishing houses and gain a better understanding of how they operate.”

The Chinese government and publishers have long sought ways to expand the readership of Chinese works in foreign markets, but the results have been slow and limited.

At London, New York, Frankfurt and other major book fairs, state-owned and private Chinese publishers display thousands of books every year, but few copyright deals ensue. It’s especially hard to crack the English-language publishing world.

The majority of translated books published by Chinese houses or small foreign ones specializing in Asian or Chinese books have tended to be scholarly endeavors rather than profitable business.

Chinese literary magazines translated, published and distributed in many languages have been slow to attract readers. In October, the magazine Chinese Literature began a publication in Arabic under the title “Beacons of the Silk Road.”

But increasing the numbers of translated Chinese books isn’t enough. Such works also need better marketing and distribution to alert foreign readers to their existence. Most translated works are hard to find in overseas bookstores and are rarely reviewed by influential literary journals.

Even at local bookshops that sell foreign-language books, those displayed most prominently are usually best-selling China books by foreign authors, such as Peter Hessler’s “Country Driving,” or they are the translations of Mo Yan’s novels after he won the Nobel Prize in 2012.

Chinese fiction has made the greatest inroads with foreign readers, especially in science fiction, crime and romance. Such novels, devoid of excessive detail on Chinese culture and history, embrace genres already popular in Western countries and have themes with universal appeal.

Popular Chinese Internet novels are helping break overseas barriers. Fans abroad often voluntarily translate the works on websites to share with non-Chinese speakers. It’s reminiscent of the way Chinese fans have often translated American TV shows to share with other Chinese.

On English-language sites featuring Internet novels, many fans say they have trouble remembering the names of Chinese characters, but the plots of romance, fantasy and intrigue are not so different from popular fiction in their own language.

Internet novels often appear in installments, with authors taking readers’ comments into account as they continue development of a plot.

In the past 10 years, Internet novels have become one of the most rapidly developing segments in Chinese publishing, involving hundreds of websites and millions of part-time or full-time writers. In recent years, many of the most popular films, TV serials and mobile games have been adaptations of Internet novels.

The genre has long been criticized for bad writing and unrealistic plots and characters, but the popularity of the segment is luring more mainstream writers and serious talent into the field. Peking University, for example, now offers classes that study the Internet novel as a literary phenomenon.