Shanghai Today

An artist renders a glowing tribute to his mentor - September 02, 2016

学生眼中的书画大家——刘一闻

EDITOR'S Note:

The Lixiang Valley Community Center provides an on-site venue in the Xinzhuang Industrial Zone for employees and nearby residents to enjoy culture exchanges.

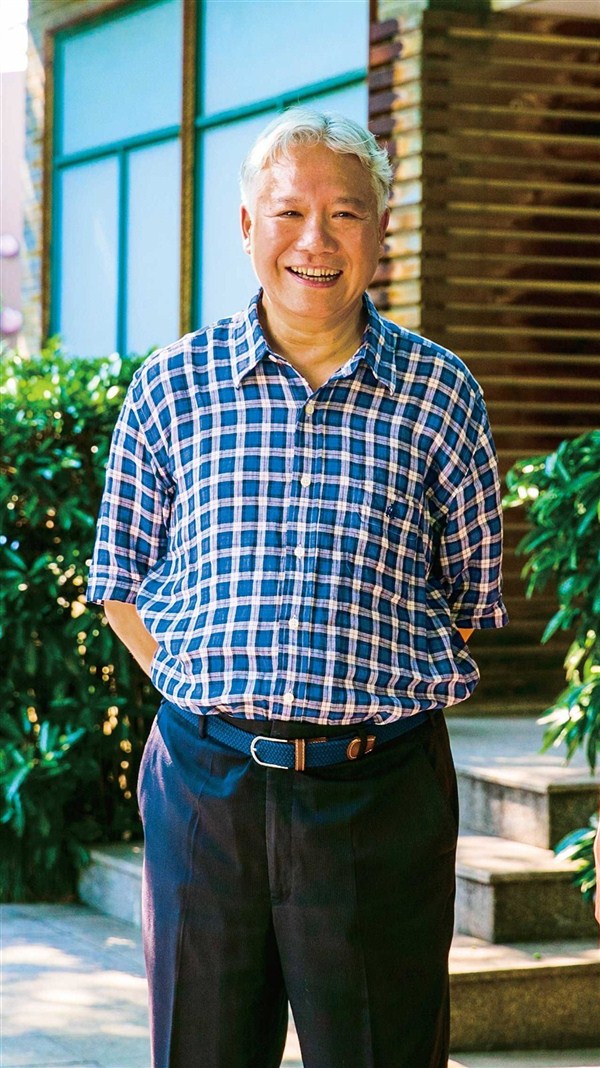

Last month, the center opened up a new institute called the Master Liu Yiwen Studio. It was named after 67-year-old Liu Yiwen, a master of calligraphy and Chinese painting.

The studio offers an array of artistic events and courses, including calligraphy, painting, the tea ceremony and Kunqu opera. Best of all, Liu and some of his pupils give lessons in art.

Shen Ailiang, one of Liu’s pupils, wrote a tribute to his teacher. We present it here as an insight into how an artisan becomes a master of his craft.

For an artist, success usually comes from four aspects: talent, lessons, diligence and opportunity. My teacher Liu Yiwen had all of them.

Liu’s paternal grandfather was Wang Xiantang, a historian and librarian in Shandong Province. The young Liu was deeply influenced by his grandfather, who had the kind of serene, calm personality essential to calligraphy and painting.

Liu told me many stories about his childhood. When he was in elementary school, he would imitate the characters he saw written on signboards, to practice the strokes.

In one class, a teacher was showing students how to write the character “一” (the numeral one). The students were told to write the character “even and straight.” But the character Liu wrote tilted upward.

When the teacher asked Liu after class why he couldn’t write the character as directed, he answered, “On the signboards, it is written with a tilt and that is better looking than straight.”

In their home, Liu’s parents had two calligraphy copybooks in a font created by ancient calligrapher Liu Gongquan (AD 778-865). Every day after school, Liu told me he spent hours practicing the font. He used ink sticks and ink stones.

“The best smell in the world is the fragrance an ink stick gives out when it is ground on an ink stone,” he said. “I’m obsessed with that smell.”

Liu met and befriended many artists in the 1970s. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-67), almost all of them were arrested or publicly denounced. Many artists had to hole up at home all day to hide from the Red Guards.

It took courage to befriend such artists in an environment where association could mean complicity with “reactionaries.” But my teacher Liu had courage. Ten artists he befriended in Shanghai became his teachers.

His first teacher was master seal-cutter Shang Chengzuo (1902-91), a friend of Liu’s grandfather. My teacher said he loved cutting seals, so when he visited Shang for the first time, he brought a seal he had cut. He had expected to be praised by the master.

But instead, Liu was admonished. “Haste makes waste,” he was told. The font Liu had used on the seal “was not unified,” Shang told him.

“No matter how good your skills, the seal is a failure,” Shang said.

Shang then explained to him where to find the proper font and pointed to reference books he could consult. Liu said he was very grateful.

“I learned why a master is a master,” he told me. “This is the power of knowledge and experience.”

Shang introduced Liu to his friends. Liu remembers them all. Like Tang Yun (1910-93), a Chinese painting master who lived in Qibao Town.

He described Tang as a “cloth-bag monk,” referring to a character in Chinese fiction.

“He sat in a cane chair, and his large body seemed to fill the room,” Liu said. “It was hard to imagine how he had gotten the nickname ‘elegant talent’ when he was young.”

The master that Liu respected the most was Su Bai (1926-83), who lived in Shandong Province. Liu corresponded with him by letters. In the beginning, they wrote each other once every two or three weeks, and then gradually, they started to correspond several times a week.

Liu saved more than 400 letters Su wrote him. They were all about art. Liu said he learned an immense amount from Su’s words and advice.

Liu was working in a factory when he learned of Su’s death. He nearly collapsed on the news. Liu’s boss refused to give him leave to attend the funeral. A big fight ensued, and Liu just picked up and left without changing out of his factory uniform.

With the help of so many masters, Liu’s works attained prominence in the 1980s. His calligraphy, seal-cutting and paintings were called the epitome of neo-classic traditional Chinese art. He started to hold exhibitions and was recognized by professional institutions.

In the 1990s, Liu became a judge in national calligraphy and seal-cutting competitions. He published books on traditional Chinese art.

I became Liu’s student in the early 1990s. What I appreciated most about him was his honesty. Like his works, he always spoke with freshness and vibrancy. I think the idiom “the style is the man” fits him perfectly.

At that time, Liu had pupils from all over the country. None of them was a beginner. Each has already achieved some fame in their genre.

Liu understood that each artist has his own style, and he never tried to impose his style on us.

Chinese painting master Qi Baishi (1864-1957) once said to his pupils, “You will have a future if you learn from me, but your future will perish if you imitate me.” The words have become a golden rule in the art world, and Liu followed the rule to the letter as an instructor.

Liu also encouraged us to be creative. Although the arts are rooted in traditional Chinese culture, he said we should not be slaves to tradition.

“Art will die if we just adhere to the past,” he often told me. “Without personal style, art cannot progress.”

Many of Liu’s students, including myself, have held their own exhibitions and have won accolades in national contests. None of us copied Liu’s style, and our works have blossomed like different varieties of flowers, each with its own fragrance.

The Lixiang Valley Community Center provides an on-site venue in the Xinzhuang Industrial Zone for employees and nearby residents to enjoy culture exchanges.

Last month, the center opened up a new institute called the Master Liu Yiwen Studio. It was named after 67-year-old Liu Yiwen, a master of calligraphy and Chinese painting.

The studio offers an array of artistic events and courses, including calligraphy, painting, the tea ceremony and Kunqu opera. Best of all, Liu and some of his pupils give lessons in art.

Shen Ailiang, one of Liu’s pupils, wrote a tribute to his teacher. We present it here as an insight into how an artisan becomes a master of his craft.

For an artist, success usually comes from four aspects: talent, lessons, diligence and opportunity. My teacher Liu Yiwen had all of them.

Liu’s paternal grandfather was Wang Xiantang, a historian and librarian in Shandong Province. The young Liu was deeply influenced by his grandfather, who had the kind of serene, calm personality essential to calligraphy and painting.

Liu told me many stories about his childhood. When he was in elementary school, he would imitate the characters he saw written on signboards, to practice the strokes.

In one class, a teacher was showing students how to write the character “一” (the numeral one). The students were told to write the character “even and straight.” But the character Liu wrote tilted upward.

When the teacher asked Liu after class why he couldn’t write the character as directed, he answered, “On the signboards, it is written with a tilt and that is better looking than straight.”

In their home, Liu’s parents had two calligraphy copybooks in a font created by ancient calligrapher Liu Gongquan (AD 778-865). Every day after school, Liu told me he spent hours practicing the font. He used ink sticks and ink stones.

“The best smell in the world is the fragrance an ink stick gives out when it is ground on an ink stone,” he said. “I’m obsessed with that smell.”

Liu met and befriended many artists in the 1970s. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-67), almost all of them were arrested or publicly denounced. Many artists had to hole up at home all day to hide from the Red Guards.

It took courage to befriend such artists in an environment where association could mean complicity with “reactionaries.” But my teacher Liu had courage. Ten artists he befriended in Shanghai became his teachers.

His first teacher was master seal-cutter Shang Chengzuo (1902-91), a friend of Liu’s grandfather. My teacher said he loved cutting seals, so when he visited Shang for the first time, he brought a seal he had cut. He had expected to be praised by the master.

But instead, Liu was admonished. “Haste makes waste,” he was told. The font Liu had used on the seal “was not unified,” Shang told him.

“No matter how good your skills, the seal is a failure,” Shang said.

Shang then explained to him where to find the proper font and pointed to reference books he could consult. Liu said he was very grateful.

“I learned why a master is a master,” he told me. “This is the power of knowledge and experience.”

Shang introduced Liu to his friends. Liu remembers them all. Like Tang Yun (1910-93), a Chinese painting master who lived in Qibao Town.

He described Tang as a “cloth-bag monk,” referring to a character in Chinese fiction.

“He sat in a cane chair, and his large body seemed to fill the room,” Liu said. “It was hard to imagine how he had gotten the nickname ‘elegant talent’ when he was young.”

The master that Liu respected the most was Su Bai (1926-83), who lived in Shandong Province. Liu corresponded with him by letters. In the beginning, they wrote each other once every two or three weeks, and then gradually, they started to correspond several times a week.

Liu saved more than 400 letters Su wrote him. They were all about art. Liu said he learned an immense amount from Su’s words and advice.

Liu was working in a factory when he learned of Su’s death. He nearly collapsed on the news. Liu’s boss refused to give him leave to attend the funeral. A big fight ensued, and Liu just picked up and left without changing out of his factory uniform.

With the help of so many masters, Liu’s works attained prominence in the 1980s. His calligraphy, seal-cutting and paintings were called the epitome of neo-classic traditional Chinese art. He started to hold exhibitions and was recognized by professional institutions.

In the 1990s, Liu became a judge in national calligraphy and seal-cutting competitions. He published books on traditional Chinese art.

I became Liu’s student in the early 1990s. What I appreciated most about him was his honesty. Like his works, he always spoke with freshness and vibrancy. I think the idiom “the style is the man” fits him perfectly.

At that time, Liu had pupils from all over the country. None of them was a beginner. Each has already achieved some fame in their genre.

Liu understood that each artist has his own style, and he never tried to impose his style on us.

Chinese painting master Qi Baishi (1864-1957) once said to his pupils, “You will have a future if you learn from me, but your future will perish if you imitate me.” The words have become a golden rule in the art world, and Liu followed the rule to the letter as an instructor.

Liu also encouraged us to be creative. Although the arts are rooted in traditional Chinese culture, he said we should not be slaves to tradition.

“Art will die if we just adhere to the past,” he often told me. “Without personal style, art cannot progress.”

Many of Liu’s students, including myself, have held their own exhibitions and have won accolades in national contests. None of us copied Liu’s style, and our works have blossomed like different varieties of flowers, each with its own fragrance.