Shanghai Today

Life in a fishing village recalled via painting - October 11, 2014

小渔村里的画家

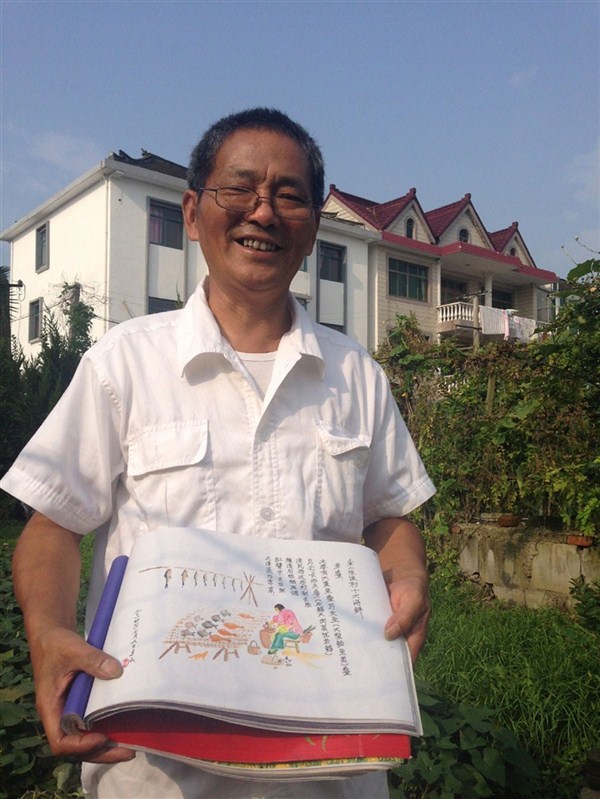

YANG Huogen has become something of a celebrity in his village in Jinshan District. The 71-year-old retired sailor living in Jinshanzui Village by the East China Sea painted to fame after his voyage life at sea.

“I’ve been dealing with the big sea all my life,” Yang said as he was showing piles of his paintings — the lively fishing scenes, the kicking crabs and the net-weaving contests.

Since his retirement in 1997, the man has painted more than 20 volumes, or almost 300 pictures, recalling his childhood anecdotes, the farming fun and his 34 years as a sailor and fisherman in the village. He has revived the traditional fishing-scene paintings common during the 1950s and 60s, such as fishermen pulling nets, catching small crabs on the beach, drying the fish and shrimp on the coastline and collecting clams in winter, among others.

In Yang’s painting “Eating Oysters,” he drew how the villagers caught and ate the delicious food. “At that time, fishermen could easily discover numerous oysters by simply moving aside the rocks on the beach. They would sit to eat them raw or collect them to sell,” Yang recalled. In the picture “Catching the Huangniluo (yellow bullacta exarata) in Summer,” the fishermen with shorts are carefully searching for a yummy-yummy in the sand, while “Collecting the Clams” vividly displays how people wearing thick clothes and hats sought those clams hidden under the mud flat in cold winter.

“I was also surprised that I could remember these things so clearly,” he said with a smile.

Fishing family

Born into a fishing family, Yang grew up by the sea with a special attachment for the deep blue marine world, even though his grandfather and father both died at sea in storms. The then little Yang was thus forbidden by his mother to learn fishing like other boys and was not even allowed to swim in the sea.

Having nothing else to do, Yang picked up tree branches to doodle on the sandy beach. “No one taught me how to paint. I just drew everything I saw by the sea,” he recalled.

When he graduated from middle school in 1961, Yang went back to the sea despite his mother’s objection. Since the age of 19, Yang sailed in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea.

He was the chef on the ship, and life was boring on the boundless sea. The young Yang started to write diaries, but he didn’t paint back then because cooking on the ship occupied most of his time.

It wasn’t until 1997 when he retired and went back home that he took up painting as a serious career. “One day when I was reading my diaries, the idea suddenly popped into my mind — why not paint them?” he said.

At the beginning, he used Chinese brushes to draw, but later he found watercolor painting was more vivid and easier to understand. He observed insects, birds, leaves, flowers, tides and waves, and he taught himself to sketch.

He made paintbrushes with bamboo and pig hair. “Because my eyesight is not good, the brushes are tailor-made for me,” Yang said.

His paintings form the memoirs of his life. He painted how his family burned ai cao (moxa grass) to dispel mosquitoes on summer nights when he was a small boy; how he was rescued by his colleagues from the sea during one voyage; how he learned to make steamed buns on the ship; how his fellow fishermen fought the sea storms and had a bumper harvest.

“It’s not how well I paint; it’s how much I enjoy painting,” he said with a smile.

In 2010, Jinshanzui Village, the Shanghai’s last fishing village in Jinshan, decided to develop a tourism attraction due to the decrease in marine resources and the urban economic reshuffling. Many fishermen in the village shelved their nets, went ashore and made their living in factories.

Painting the fishing traditions

That year, Yang started to paint the fishing village, the fishermen and the fishing traditions that were dying out.

“Today’s children know nothing about how we fished before. I painted them and hope those pictures can at least be a witness of the past days,” Yang said.

The artist now lives in a two-story farmhouse with a small garden in the backyard, where he grows garlic, potatoes, beans, gourds, celery and cabbage. He also raises four ducks in the nearby pond.

Yang doesn’t drink but smokes. Collecting cigarette boxes is the old man’s other big hobby. Since his sailor life, Yang has collected more than 10,000 cigarette boxes, ranging from Double Happiness, Chienmen Grande, Shanquan (a cigarette produced in Guizhou Province) to Hongtashan, Camellia and Yellow Rose.

Life is carefree. When Yang is in good spirits, he can keep painting for almost eight hours a day; if he is busy taking care of his ducks and vegetables, he just pauses but always returns to his art work.

In 2012, he was invited to illustrate for a book on Jinshan’s fishing history. Within five days, Yang painted 18 illustrations, completely reflecting the fishing traditions in the village. Today all the illustrations are on display at the Jinshanzui Village Museum.

On sunny days, Yang goes out for a walk along the coastline and buys some fresh seafood from his fellow villagers, who are still fishing for a pastime.

“We talk about the days of yore and exchange those sailing and fishing stories,” he said. “Just like painting, it’s our way to recall the past. It’s still fun.”

“I’ve been dealing with the big sea all my life,” Yang said as he was showing piles of his paintings — the lively fishing scenes, the kicking crabs and the net-weaving contests.

Since his retirement in 1997, the man has painted more than 20 volumes, or almost 300 pictures, recalling his childhood anecdotes, the farming fun and his 34 years as a sailor and fisherman in the village. He has revived the traditional fishing-scene paintings common during the 1950s and 60s, such as fishermen pulling nets, catching small crabs on the beach, drying the fish and shrimp on the coastline and collecting clams in winter, among others.

In Yang’s painting “Eating Oysters,” he drew how the villagers caught and ate the delicious food. “At that time, fishermen could easily discover numerous oysters by simply moving aside the rocks on the beach. They would sit to eat them raw or collect them to sell,” Yang recalled. In the picture “Catching the Huangniluo (yellow bullacta exarata) in Summer,” the fishermen with shorts are carefully searching for a yummy-yummy in the sand, while “Collecting the Clams” vividly displays how people wearing thick clothes and hats sought those clams hidden under the mud flat in cold winter.

“I was also surprised that I could remember these things so clearly,” he said with a smile.

Fishing family

Born into a fishing family, Yang grew up by the sea with a special attachment for the deep blue marine world, even though his grandfather and father both died at sea in storms. The then little Yang was thus forbidden by his mother to learn fishing like other boys and was not even allowed to swim in the sea.

Having nothing else to do, Yang picked up tree branches to doodle on the sandy beach. “No one taught me how to paint. I just drew everything I saw by the sea,” he recalled.

When he graduated from middle school in 1961, Yang went back to the sea despite his mother’s objection. Since the age of 19, Yang sailed in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea.

He was the chef on the ship, and life was boring on the boundless sea. The young Yang started to write diaries, but he didn’t paint back then because cooking on the ship occupied most of his time.

It wasn’t until 1997 when he retired and went back home that he took up painting as a serious career. “One day when I was reading my diaries, the idea suddenly popped into my mind — why not paint them?” he said.

At the beginning, he used Chinese brushes to draw, but later he found watercolor painting was more vivid and easier to understand. He observed insects, birds, leaves, flowers, tides and waves, and he taught himself to sketch.

He made paintbrushes with bamboo and pig hair. “Because my eyesight is not good, the brushes are tailor-made for me,” Yang said.

His paintings form the memoirs of his life. He painted how his family burned ai cao (moxa grass) to dispel mosquitoes on summer nights when he was a small boy; how he was rescued by his colleagues from the sea during one voyage; how he learned to make steamed buns on the ship; how his fellow fishermen fought the sea storms and had a bumper harvest.

“It’s not how well I paint; it’s how much I enjoy painting,” he said with a smile.

In 2010, Jinshanzui Village, the Shanghai’s last fishing village in Jinshan, decided to develop a tourism attraction due to the decrease in marine resources and the urban economic reshuffling. Many fishermen in the village shelved their nets, went ashore and made their living in factories.

Painting the fishing traditions

That year, Yang started to paint the fishing village, the fishermen and the fishing traditions that were dying out.

“Today’s children know nothing about how we fished before. I painted them and hope those pictures can at least be a witness of the past days,” Yang said.

The artist now lives in a two-story farmhouse with a small garden in the backyard, where he grows garlic, potatoes, beans, gourds, celery and cabbage. He also raises four ducks in the nearby pond.

Yang doesn’t drink but smokes. Collecting cigarette boxes is the old man’s other big hobby. Since his sailor life, Yang has collected more than 10,000 cigarette boxes, ranging from Double Happiness, Chienmen Grande, Shanquan (a cigarette produced in Guizhou Province) to Hongtashan, Camellia and Yellow Rose.

Life is carefree. When Yang is in good spirits, he can keep painting for almost eight hours a day; if he is busy taking care of his ducks and vegetables, he just pauses but always returns to his art work.

In 2012, he was invited to illustrate for a book on Jinshan’s fishing history. Within five days, Yang painted 18 illustrations, completely reflecting the fishing traditions in the village. Today all the illustrations are on display at the Jinshanzui Village Museum.

On sunny days, Yang goes out for a walk along the coastline and buys some fresh seafood from his fellow villagers, who are still fishing for a pastime.

“We talk about the days of yore and exchange those sailing and fishing stories,” he said. “Just like painting, it’s our way to recall the past. It’s still fun.”