Shanghai Today

A man of many words leaves a lasting legacy - February 13, 2015

老人用36年自编首部汉语—普什图语辞典

THE 19th century French author Alexander Dumas once wrote that the “mastery of language affords one remarkable opportunities.”

For Professor Che Hongcai, fluency in Pashtu, the official language of Afghanistan, opened the door to a remarkable opportunity that took him 36 years to fulfill.

His magnum opus, a two-million word Pashtu-Chinese dictionary, arrived in bookstores this month. It is the first of its kind ever published.

“A person needs to accomplish at least one meaningful thing in his life,” Che says. “This dictionary became my lifelong dream.”

Its publication coincides with the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Afghanistan. Professor Che was in Kabul early this week for celebrations marking the milestone. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, praising the Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary as a “sign of friendship” between both countries, awarded him a national medal.

Che’s crowning achievement instills pride in all those who helped him along the way. I count myself among the fortunate, though lowly, associates.

In 2004, I was a student of Professor Che’s at the Beijing Broadcasting Institute, since renamed the Communication University of China. I was among 19 students studying both English and Pashtu.

In my senior year, Che asked several of us to help him find a way to input Pashtu on a computer because his stacks of printed reference cards had become too unwieldy.

At the time, I never dreamed that this task was part of such a grand mission.

Now, all these years later, as I stood in front of his university apartment in Beijing, preparing to interview him about the dictionary’s publication, I felt my knees tremble a bit.

The dictionary, published by Commercial Press, isn’t one of those books that will go flying off the shelves. Very few Chinese are even aware of Pashtu.

The national language of Afghanistan is mainly spoken in the east and south of the country and also in the northwestern region of Pakistan. Since the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949, it’s estimated that less than 150 Chinese people have learned to speak and write the language, and only about 30 frequently use it in their work.

As I sat opposite my old professor, now 78, in his home, the memory of my student days with him came flooding back.

“Can you help me find on the Internet how to input Pashtu?” I remember his asking. “My Pashtu cards are too old to store and use. I want to type them into a computer.”

We students had, in fact, heard about these mysterious Pashtu cards. After a week of research, we found a somewhat arcane method for putting them online and installed the system for him.

That was the first time we got a glimpse of the legendary cards. Each was 15cm by 10cm in size, and full of Pashtu characters, pinyin translations and grammatical references. Some were already turning yellow and becoming tattered. When we tried to examine them more closely, Che seized them from us, holding them close as if we were going to steal a baby from his arms.

At that time, we didn’t know that the cards were the beginning of a major project by Che and another Pashtu scholar, Song Qiangmin. They were using a Pashtu-Russian dictionary to copy entries onto 100,000 handwritten cards. The cards eventually filled 30 wooden boxes and came to comprise about 70 percent of the words Che finally compiled into the newly published Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary.

After several days, Che summoned me and four classmates to his office. He asked us to input the information on the cards into a computer as our graduation work. So we each picked up five or six cards and took them back to our dormitory. The characters were written on the cards in a small, neat hand. Although we had studied Pashtu for four years, many of the words still puzzled us. The typing task was harder than we had imagined. We submitted our first batch of work to Che, and that was the last time we ever heard of the typing project.

Now, sitting opposite the professor at his home, he explains what happened. Too many people involved in the work led to inconsistencies and mistakes, he says.

“I decided I couldn’t quite trust my grand effort to you students,” he says. “So I decided to do it myself.”

It took years to put 50,000 vocabulary entries, altogether 2.5 million words, into the computer. During that time, Che underwent two surgeries for detached retinas that almost left him blind.

“A lot of media, both local and foreign, have come to interview me recently, praising the great work I have done,” the gray-haired Che says. “I am really flattered. Some even wanted to make a film about me. But I don’t think what I did was such a big deal. It was just what I had to do.”

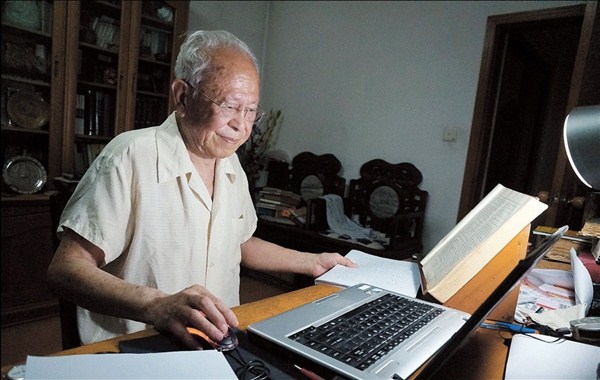

Age has slowed him little. Che was still at his desk, typing, editing and proofreading, when I arrived. His wife ushered me into his study. The furniture and interior décor were just as I remembered from 10 years earlier. A large cabinet holding all those card boxes still sat in a corner.

Che says the dictionary started as a national assignment but was forgotten by officials over the years.

Today it stands as testament to the fact that the world of lexicography and scholarship will never forget the achievement.

On a bookshelf at Che’s home is a certificate that documents where his life’s quest began. Written in Pashtu and English, it’s a graduation diploma from Kabul University, where Che learned Pashtu.

He was sent to study in Afghanistan following the historic Bandung Conference in 1955, when China first started forging diplomatic relations with newly independent countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. At that time, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was concerned about the lack of translators and interpreters in foreign languages and sent Chinese students abroad to study.

A junior at the Beijing Foreign Studies University, Che was sent on a four-year exchange program to the Cultural Institute of Kabul University.

After three years of study, Che returned home and began teaching Pashtu at what is now the Communication University of China.

As an expert in the language, Che was frequently seconded to various national government departments. He did broadcasts for China Radio International and helped translate government documents. In 1975, the State Council, China’s cabinet, commissioned a massive project to compile 160 dictionaries of foreign languages into Chinese. The Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary was one of them.

The project, begun in the late 1970s, was assigned to Che and Song. Che says he regarded the mission as a great honor and was confident it could be completed in a few years. The pair were helped by Zhang Min, a staff member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“We had a passion for the assignment, and we wanted to do it perfectly,” Zhang recalls.

There was no funding for the project. Che had to borrow a Pashtu typewriter and picked up scrap paper from a printing plant to make his index cards. On each, he wrote a Pashtu word followed by a phonetic notation, its part of speech and a paraphrase of its meaning. The job was tedious, even boring. Che and Song worked long days. Sometimes complex words could take hours to process, resulting in just a few cards being completed in one day.

In 1981, about 70 percent through their work, the university asked Che to set aside the dictionary project temporarily and help it design a new correspondence course. He did that for six years.

In 1989, he was appointed as an envoy to Pakistan, and then to Afghanistan. That meant leaving the dictionary project and going on the diplomatic circuit of banquets and formal ceremonies. But his mind never left all those cards stored away in boxes.

In 1992, civil war in Afghanistan resulted in an attack on the Chinese Embassy in Kabul. The embassy was closed and Che returned to China.

By that time, the dictionary project had been forgotten by government officials. In 2000, Song died. Che was discouraged.

“He felt the world had forgotten him,” says Che’s wife, Xue Ping. “He was so upset that he went silent for long periods of time.”

Oddly enough for Che’s project, it was the September 11 attacks in the United States that reinvigorated the dictionary project. Attention was refocused on war-torn Afghanistan. The US government, realizing it faced a shortage of Pashtu-language experts, began recruiting fluent speakers from around the world.

The dearth of bilingual talent was also recognized in China. The Communication University of China invited Che back to teach Pashtu. Increasing bilateral exchanges between China and Afghanistan convinced Che that his dictionary project was vital and needed to be completed.

He invited Zhang to help with proofing the text. Another four years passed before the hefty draft was completed in 2012 and delivered to Commercial Press.

Zhang Wenying, director of the editorial office at Commercial Press, took over the job of publication. She says she was surprised to learn from the archives that the project had started so long ago and marveled at the accomplishment.

“The dictionary was just my destiny in the river of history,” Che says. “Compiling a dictionary requires tenacity. It doesn’t allow you to hesitate or slack off. In the end, a dictionary can have a lasting and profound influence.”

For Professor Che Hongcai, fluency in Pashtu, the official language of Afghanistan, opened the door to a remarkable opportunity that took him 36 years to fulfill.

His magnum opus, a two-million word Pashtu-Chinese dictionary, arrived in bookstores this month. It is the first of its kind ever published.

“A person needs to accomplish at least one meaningful thing in his life,” Che says. “This dictionary became my lifelong dream.”

Its publication coincides with the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Afghanistan. Professor Che was in Kabul early this week for celebrations marking the milestone. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, praising the Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary as a “sign of friendship” between both countries, awarded him a national medal.

Che’s crowning achievement instills pride in all those who helped him along the way. I count myself among the fortunate, though lowly, associates.

In 2004, I was a student of Professor Che’s at the Beijing Broadcasting Institute, since renamed the Communication University of China. I was among 19 students studying both English and Pashtu.

In my senior year, Che asked several of us to help him find a way to input Pashtu on a computer because his stacks of printed reference cards had become too unwieldy.

At the time, I never dreamed that this task was part of such a grand mission.

Now, all these years later, as I stood in front of his university apartment in Beijing, preparing to interview him about the dictionary’s publication, I felt my knees tremble a bit.

The dictionary, published by Commercial Press, isn’t one of those books that will go flying off the shelves. Very few Chinese are even aware of Pashtu.

The national language of Afghanistan is mainly spoken in the east and south of the country and also in the northwestern region of Pakistan. Since the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949, it’s estimated that less than 150 Chinese people have learned to speak and write the language, and only about 30 frequently use it in their work.

As I sat opposite my old professor, now 78, in his home, the memory of my student days with him came flooding back.

“Can you help me find on the Internet how to input Pashtu?” I remember his asking. “My Pashtu cards are too old to store and use. I want to type them into a computer.”

We students had, in fact, heard about these mysterious Pashtu cards. After a week of research, we found a somewhat arcane method for putting them online and installed the system for him.

That was the first time we got a glimpse of the legendary cards. Each was 15cm by 10cm in size, and full of Pashtu characters, pinyin translations and grammatical references. Some were already turning yellow and becoming tattered. When we tried to examine them more closely, Che seized them from us, holding them close as if we were going to steal a baby from his arms.

At that time, we didn’t know that the cards were the beginning of a major project by Che and another Pashtu scholar, Song Qiangmin. They were using a Pashtu-Russian dictionary to copy entries onto 100,000 handwritten cards. The cards eventually filled 30 wooden boxes and came to comprise about 70 percent of the words Che finally compiled into the newly published Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary.

After several days, Che summoned me and four classmates to his office. He asked us to input the information on the cards into a computer as our graduation work. So we each picked up five or six cards and took them back to our dormitory. The characters were written on the cards in a small, neat hand. Although we had studied Pashtu for four years, many of the words still puzzled us. The typing task was harder than we had imagined. We submitted our first batch of work to Che, and that was the last time we ever heard of the typing project.

Now, sitting opposite the professor at his home, he explains what happened. Too many people involved in the work led to inconsistencies and mistakes, he says.

“I decided I couldn’t quite trust my grand effort to you students,” he says. “So I decided to do it myself.”

It took years to put 50,000 vocabulary entries, altogether 2.5 million words, into the computer. During that time, Che underwent two surgeries for detached retinas that almost left him blind.

“A lot of media, both local and foreign, have come to interview me recently, praising the great work I have done,” the gray-haired Che says. “I am really flattered. Some even wanted to make a film about me. But I don’t think what I did was such a big deal. It was just what I had to do.”

Age has slowed him little. Che was still at his desk, typing, editing and proofreading, when I arrived. His wife ushered me into his study. The furniture and interior décor were just as I remembered from 10 years earlier. A large cabinet holding all those card boxes still sat in a corner.

Che says the dictionary started as a national assignment but was forgotten by officials over the years.

Today it stands as testament to the fact that the world of lexicography and scholarship will never forget the achievement.

On a bookshelf at Che’s home is a certificate that documents where his life’s quest began. Written in Pashtu and English, it’s a graduation diploma from Kabul University, where Che learned Pashtu.

He was sent to study in Afghanistan following the historic Bandung Conference in 1955, when China first started forging diplomatic relations with newly independent countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. At that time, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was concerned about the lack of translators and interpreters in foreign languages and sent Chinese students abroad to study.

A junior at the Beijing Foreign Studies University, Che was sent on a four-year exchange program to the Cultural Institute of Kabul University.

After three years of study, Che returned home and began teaching Pashtu at what is now the Communication University of China.

As an expert in the language, Che was frequently seconded to various national government departments. He did broadcasts for China Radio International and helped translate government documents. In 1975, the State Council, China’s cabinet, commissioned a massive project to compile 160 dictionaries of foreign languages into Chinese. The Pashtu-Chinese Dictionary was one of them.

The project, begun in the late 1970s, was assigned to Che and Song. Che says he regarded the mission as a great honor and was confident it could be completed in a few years. The pair were helped by Zhang Min, a staff member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“We had a passion for the assignment, and we wanted to do it perfectly,” Zhang recalls.

There was no funding for the project. Che had to borrow a Pashtu typewriter and picked up scrap paper from a printing plant to make his index cards. On each, he wrote a Pashtu word followed by a phonetic notation, its part of speech and a paraphrase of its meaning. The job was tedious, even boring. Che and Song worked long days. Sometimes complex words could take hours to process, resulting in just a few cards being completed in one day.

In 1981, about 70 percent through their work, the university asked Che to set aside the dictionary project temporarily and help it design a new correspondence course. He did that for six years.

In 1989, he was appointed as an envoy to Pakistan, and then to Afghanistan. That meant leaving the dictionary project and going on the diplomatic circuit of banquets and formal ceremonies. But his mind never left all those cards stored away in boxes.

In 1992, civil war in Afghanistan resulted in an attack on the Chinese Embassy in Kabul. The embassy was closed and Che returned to China.

By that time, the dictionary project had been forgotten by government officials. In 2000, Song died. Che was discouraged.

“He felt the world had forgotten him,” says Che’s wife, Xue Ping. “He was so upset that he went silent for long periods of time.”

Oddly enough for Che’s project, it was the September 11 attacks in the United States that reinvigorated the dictionary project. Attention was refocused on war-torn Afghanistan. The US government, realizing it faced a shortage of Pashtu-language experts, began recruiting fluent speakers from around the world.

The dearth of bilingual talent was also recognized in China. The Communication University of China invited Che back to teach Pashtu. Increasing bilateral exchanges between China and Afghanistan convinced Che that his dictionary project was vital and needed to be completed.

He invited Zhang to help with proofing the text. Another four years passed before the hefty draft was completed in 2012 and delivered to Commercial Press.

Zhang Wenying, director of the editorial office at Commercial Press, took over the job of publication. She says she was surprised to learn from the archives that the project had started so long ago and marveled at the accomplishment.

“The dictionary was just my destiny in the river of history,” Che says. “Compiling a dictionary requires tenacity. It doesn’t allow you to hesitate or slack off. In the end, a dictionary can have a lasting and profound influence.”